Exercise Solutions

Model selection with the Loyn data

In the previous exercise you fitted a pre-conceived model which

included the main effects of the area of the forest patch

(LOGAREA), the grazing intensity (FGRAZE) and

the interaction between these two explanatory variables

(FGRAZE:LOGAREA). This was useful as a training exercise,

and might be a viable approach when analysing these data if the

experiment had been designed to test these effects only. However, if

other potentially important variables are not included in the model this

may lead to biased inferences (interpretation). Additionally, if the

goal of the analysis is to explore what models explain the data in a

parsimonious way (as opposed to formally testing hypotheses), we would

also want to include relevant additional explanatory variables.

Here we revisit the previous loyn data analysis, and ask if a

‘better’ model for these data could be achieved by including additional

explanatory variables and by performing model selection. Because we

would like to test the significance of the interaction between

LOGAREA, and FGRAZE, whilst accounting for the

potential effects of other explanatory variables, we will also include

LOGAREA, FGRAZE and their interaction in the

model as before. Including other interaction terms between other

variables may be reasonable, but we will focus only on the

FGRAZE:LOGAREA interaction as we have relatively little

information in this data set (67 observations). This will hopefully

avoid fitting an overly complex model which will estimate many

parameters for which we have very little data. This is a balance you

will all have to maintain with your own data and analyses (or better

still, perform a power analysis before you even collect your data). No

4-way interaction terms in your models please!

It’s also important to note that we will assume that all the explanatory variables were collected by the researchers because they believed them to be biologically relevant for explaining bird abundance (i.e. data were collected for a reason). Of course, this is probably not your area of expertise but it is nevertheless a good idea to pause and think what might be relevant or not-so relevant and why. This highlights the importance of knowing your study organism / study area and discussing research designs with colleagues and other experts in the field before you collect your data. What you should try to avoid is collecting heaps of data across many variables (just because you can) and then expecting your statistical models to make sense of it for you. As mentioned in the lecture, model selection is a relatively controversial topic and should not be treated as a purely mechanical process. Your expertise needs to be woven into this process otherwise you may end up with a model that is implausible or not very useful (and all models need to be useful!).

1. Import the ‘loyn.txt’ data file into RStudio and assign it to a

variable called loyn. Here we will be using all the

explanatory variables to explain the variation in bird density. If

needed, remind yourself of your data exploration you conducted

previously. Do any of the remaining variables need transforming

(i.e. AREA, DIST, LDIST) or

converting to a factor type variable (i.e. GRAZE)? Add the

transformed variables to the loyn dataframe.

loyn <- read.table("data/loyn.txt", header = TRUE)

str(loyn)

## 'data.frame': 67 obs. of 8 variables:

## $ SITE : int 1 60 2 3 61 4 5 6 7 8 ...

## $ ABUND : num 5.3 10 2 1.5 13 17.1 13.8 14.1 3.8 2.2 ...

## $ AREA : num 0.1 0.2 0.5 0.5 0.6 1 1 1 1 1 ...

## $ DIST : int 39 142 234 104 191 66 246 234 467 284 ...

## $ LDIST : int 39 142 234 311 357 66 246 285 467 1829 ...

## $ YR.ISOL: int 1968 1961 1920 1900 1957 1966 1918 1965 1955 1920 ...

## $ GRAZE : int 2 2 5 5 2 3 5 3 5 5 ...

## $ ALT : int 160 180 60 140 185 160 140 130 90 60 ...

loyn$LOGAREA <- log10(loyn$AREA)

loyn$LOGDIST <- log10(loyn$DIST)

loyn$LOGLDIST <- log10(loyn$LDIST)

# create factor GRAZE as it was originally coded as an integer

loyn$FGRAZE <- factor(loyn$GRAZE)

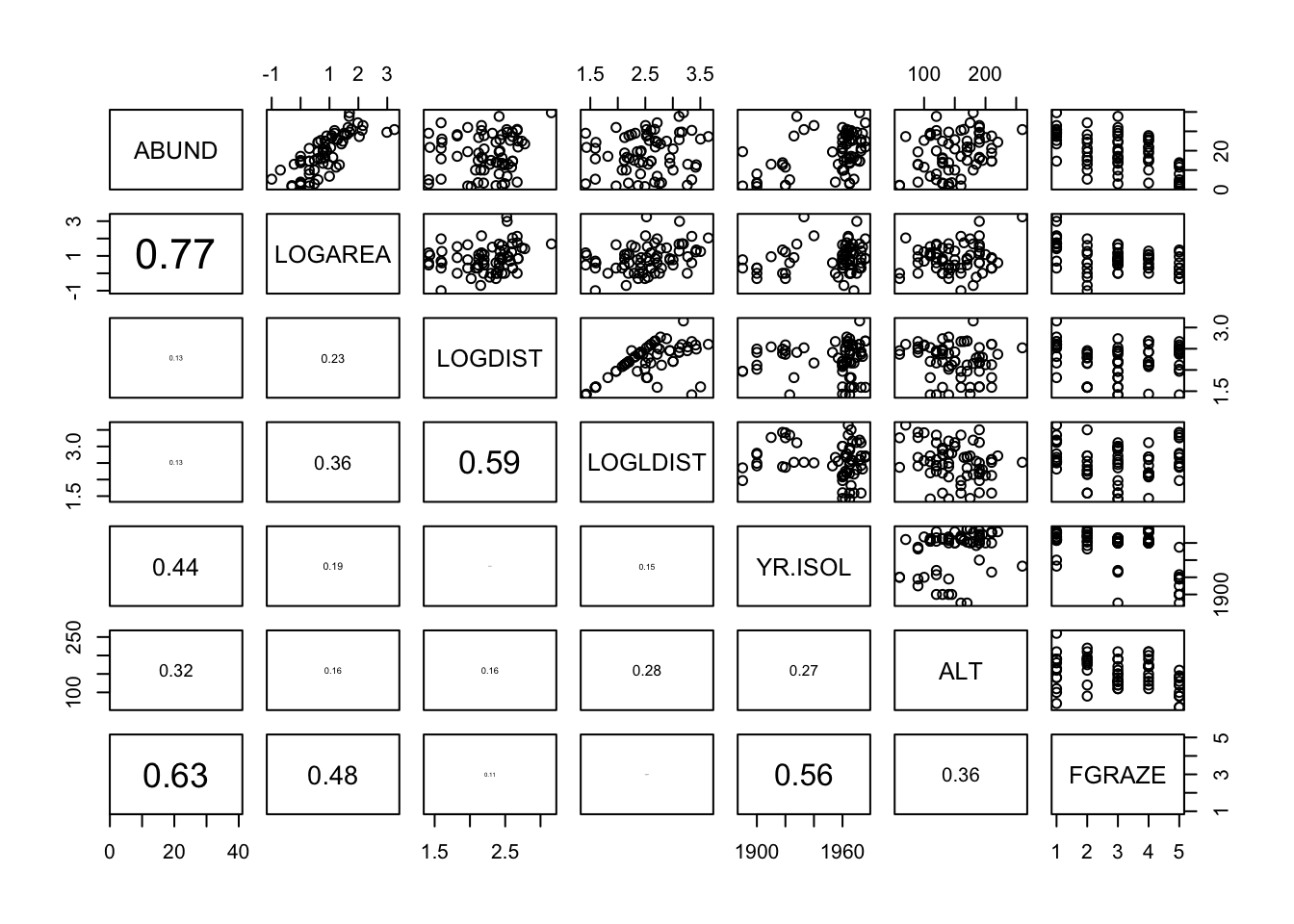

2. Let’s start with a very quick graphical exploration of any

potential relationships between each explanatory variable (collinearity)

and also between our response and explanatory variables (what we’re

interested in). Create a pairs plot using the function

pairs()of your variables of interest. Hint: restrict the

plot to the variables you actually need. An effective way of doing this

is to store the names of the variables of interest in a vector

VOI <- c("Var1", "Var2", ...) and then use the naming

method for subsetting the data set Mydata[, VOI]. If you

feel like it, you can also add the correlations to the lower triangle of

the plot as you did previously (don’t forget to define the function

first).

# define the panel.cor function from ?pairs

panel.cor <- function(x, y, digits = 2, prefix = "", cex.cor, ...)

{

usr <- par("usr")

par(usr = c(0, 1, 0, 1))

r <- abs(cor(x, y))

txt <- format(c(r, 0.123456789), digits = digits)[1]

txt <- paste0(prefix, txt)

if(missing(cex.cor)) cex.cor <- 0.8/strwidth(txt)

text(0.5, 0.5, txt, cex = cex.cor * r)

}

# subset the variables of interest

VOI<- c("ABUND", "LOGAREA", "LOGDIST", "LOGLDIST", "YR.ISOL", "ALT", "FGRAZE")

pairs(loyn[, VOI], lower.panel = panel.cor)

# There are varying degrees of correlation between explanatory variables which

# might indicate some collinearity, i.e. LOGAREA and FGRAZE (0.48), LOGDIST and

# LOGLDIST (0.59) and YR.ISOL and FGRAZE (0.56). However, the relationships

# between these explanatory variables are quite weak so we can probably

# include these variables in the same model (but keep an eye on things).

# There also seems to be a reasonable spread of observations across these

# pairs of explanatory variables.

# The relationship between the response variable ABUND and all the explanatory

# variables is visible in the top row:

# Some potential relationships present like with LOGAREA (positive),

# maybe ALT (positive) and FGRAZE (negative).

3. Now, let’s fit our maximal model. Start with a model of

ABUND and include all explanatory variables as main

effects. Also include the interaction LOGAREA:FGRAZE but no

other interaction terms as justified in the preamble above. Don’t forget

to include the transformed versions of the variables where appropriate

(but not the untransformed variables as well otherwise you will have

very strong collinearity between these variables!). Perhaps, call this

model M1.

M1 <- lm(ABUND ~ LOGDIST + LOGLDIST + YR.ISOL + ALT + LOGAREA + FGRAZE +

FGRAZE:LOGAREA, data = loyn)

4. Have a look at the summary table of the model using the

summary() function. You’ll probably find this summary is

quite complicated with lots of parameter estimates (14) and P values

testing lots of hypotheses. Are all the P values less than our cut-off

of 0.05? If not, then this suggests that some form of model selection is

warranted to simplify our model.

summary(M1)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = ABUND ~ LOGDIST + LOGLDIST + YR.ISOL + ALT + LOGAREA +

## FGRAZE + FGRAZE:LOGAREA, data = loyn)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -14.976 -1.972 0.142 2.388 10.631

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 33.963217 93.824477 0.362 0.71880

## LOGDIST 0.882214 2.204341 0.400 0.69061

## LOGLDIST -0.253543 1.709295 -0.148 0.88264

## YR.ISOL -0.008283 0.047374 -0.175 0.86186

## ALT 0.016979 0.018630 0.911 0.36622

## LOGAREA 3.733668 1.914379 1.950 0.05643 .

## FGRAZE2 -6.757424 4.132084 -1.635 0.10790

## FGRAZE3 -12.488020 4.542801 -2.749 0.00816 **

## FGRAZE4 -16.133695 4.838990 -3.334 0.00157 **

## FGRAZE5 -17.191221 4.991340 -3.444 0.00113 **

## LOGAREA:FGRAZE2 4.877440 2.565757 1.901 0.06275 .

## LOGAREA:FGRAZE3 9.410212 3.223378 2.919 0.00514 **

## LOGAREA:FGRAZE4 14.166912 4.304081 3.292 0.00178 **

## LOGAREA:FGRAZE5 2.617845 3.347001 0.782 0.43761

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 5.009 on 53 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.8034, Adjusted R-squared: 0.7551

## F-statistic: 16.66 on 13 and 53 DF, p-value: 2.644e-14

5. Let’s perform a first step in model selection using the

drop1() function and use an F test based model

selection approach. This will allow us to decide which explanatory

variables may be suitable for removal from the model. Remember to use

the test = "F" argument to perform F tests when

using drop1(). Which explanatory variable is the best

candidate for removal and why? What hypothesis is being tested when we

do this model selection step?

# Wait: why can't we use information from the 'summary(M1)' or 'anova(M1)' functions

# to do this?

# the 'summary' table tests if the coefficient for each explanatory variable

# is significantly different from zero.

# the 'anova' tests for the significance of the proportion of variation explained

# by a particular term in the model.

# The ANOVA table also allows testing the overall significance of a categorical explanatory

# variable (like FGRAZE) which involves several parameters together (one for each level),

# which is quite is handy. But the results of this ANOVA are based on sequential

# sums of squares and therefore the order of the variables in the model

# (which is arbitrary here) matters.

# We could change the order but there are too many possible permutations.

# Summary P values don't suffer from this problem but tests different hypotheses.

# It would be useful to use an ANOVA that doesn't depend on the order

# of inclusion of the variables, this is effectively what 'drop1' does.

drop1(M1, test = "F")

## Single term deletions

##

## Model:

## ABUND ~ LOGDIST + LOGLDIST + YR.ISOL + ALT + LOGAREA + FGRAZE +

## FGRAZE:LOGAREA

## Df Sum of Sq RSS AIC F value Pr(>F)

## <none> 1329.8 228.20

## LOGDIST 1 4.02 1333.8 226.40 0.1602 0.690605

## LOGLDIST 1 0.55 1330.3 226.23 0.0220 0.882644

## YR.ISOL 1 0.77 1330.6 226.24 0.0306 0.861862

## ALT 1 20.84 1350.6 227.24 0.8306 0.366220

## LOGAREA:FGRAZE 4 405.04 1734.8 238.02 4.0358 0.006259 **

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

# LOGLDIST is the least significant (p = 0.88), and therefore makes the least

# contribution to the variability explained by the model, with respect to

# the number of degrees of freedom it uses (1)

6. Update and refit your model and remove the least significant

explanatory variable (from above). Repeat single term deletions with

drop1() again using this updated model. You can update the

model by just fitting a new model without the appropriate explanatory

variable and assign it to a new name (M2). Alternatively

you can use the update() function instead. I’ll show you

both ways in the solutions below.

# new model removing LOGLDIST

M2 <- lm(ABUND ~ LOGDIST + YR.ISOL + ALT + LOGAREA + FGRAZE +

LOGAREA:FGRAZE, data = loyn)

# or use a shortcut with the update() function:

M2 <- update(M1, formula = . ~ . - LOGLDIST) # "." means all previous variables

# now redo drop1() on the new model

drop1(M2, test = "F")

## Single term deletions

##

## Model:

## ABUND ~ LOGDIST + YR.ISOL + ALT + LOGAREA + FGRAZE + LOGAREA:FGRAZE

## Df Sum of Sq RSS AIC F value Pr(>F)

## <none> 1330.3 226.23

## LOGDIST 1 3.64 1334.0 224.41 0.1478 0.702134

## YR.ISOL 1 0.78 1331.1 224.27 0.0317 0.859332

## ALT 1 22.24 1352.6 225.34 0.9029 0.346233

## LOGAREA:FGRAZE 4 406.74 1737.1 236.10 4.1275 0.005451 **

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

# YR.ISOL is now the least significant (p = 0.859), hence makes the least

# contribution to the variability explained by the model,

# with respect to the number of degrees of freedom it uses (1)

7. Again, update the model to remove the least significant

explanatory variable (from above) and repeat single term deletions with

drop1().

M3 <- update(M2, formula = . ~ . - YR.ISOL)

drop1(M3, test = "F")

## Single term deletions

##

## Model:

## ABUND ~ LOGDIST + ALT + LOGAREA + FGRAZE + LOGAREA:FGRAZE

## Df Sum of Sq RSS AIC F value Pr(>F)

## <none> 1331.1 224.27

## LOGDIST 1 3.28 1334.4 222.43 0.1355 0.714237

## ALT 1 25.33 1356.5 223.53 1.0468 0.310729

## LOGAREA:FGRAZE 4 405.99 1737.1 234.10 4.1936 0.004916 **

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

# LOGDIST now the least significant (p = 0.714) and should be removed from

# the next model.

8. Once again, update the model to remove the least significant

explanatory variable (from above) and repeat single term deletions with

drop1().

M4 <- update(M3, formula = . ~ . - LOGDIST)

drop1(M4, test = "F")

## Single term deletions

##

## Model:

## ABUND ~ ALT + LOGAREA + FGRAZE + LOGAREA:FGRAZE

## Df Sum of Sq RSS AIC F value Pr(>F)

## <none> 1334.4 222.43

## ALT 1 22.84 1357.2 221.57 0.9584 0.331805

## LOGAREA:FGRAZE 4 408.56 1743.0 232.33 4.2864 0.004273 **

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

# ALT is not significant (p = 0.331)

9. And finally, update the model to remove the least significant

explanatory variable (from above) and repeat single term deletions with

drop1().

# and finally drop ALT from the model

M5 <- update(M4, formula = . ~ . - ALT)

drop1(M5, test = "F")

## Single term deletions

##

## Model:

## ABUND ~ LOGAREA + FGRAZE + LOGAREA:FGRAZE

## Df Sum of Sq RSS AIC F value Pr(>F)

## <none> 1357.2 221.57

## LOGAREA:FGRAZE 4 389.3 1746.6 230.47 4.0874 0.00556 **

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

# the LOGAREA:FGRAZE term represents the interaction between LOGAREA and

# FGRAZE. This is significant (p = 0.005) and so our model selection

# process comes to an end.

10. If all goes well, your final model should be

lm(ABUND ~ LOGAREA + FGRAZE + LOGAREA:FGRAZE) which you

encountered in the previous exercise. Also, you may have noticed that

the output from the drop1() function does not include the

main effects of LOGAREA or FRGRAZE. Can you

think why this might be the case?

# As the interaction between LOGAREA and FGRAZE was significant at each step of

# model selection process the main effects should be left in our model,

# irrespective of significance. This is because it is quite difficult to

# interpret an interaction without the main effects. The drop1

# function is clever enough that it doesn't let you see the P values for the

# main effects, in the presence of their significant interaction.

# Also note, because R always includes interactions *after* their main effects

# the P value of the interaction term (p = 0.005) from the model selection

# is the same as P value if we use the anova() function on our final model

# Check this:

anova(M5)

## Analysis of Variance Table

##

## Response: ABUND

## Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

## LOGAREA 1 3978.1 3978.1 167.0669 < 2.2e-16 ***

## FGRAZE 4 1038.2 259.5 10.9000 1.241e-06 ***

## LOGAREA:FGRAZE 4 389.3 97.3 4.0874 0.00556 **

## Residuals 57 1357.3 23.8

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

drop1(M5, test= "F")

## Single term deletions

##

## Model:

## ABUND ~ LOGAREA + FGRAZE + LOGAREA:FGRAZE

## Df Sum of Sq RSS AIC F value Pr(>F)

## <none> 1357.2 221.57

## LOGAREA:FGRAZE 4 389.3 1746.6 230.47 4.0874 0.00556 **

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

11. Now that you have your final model, you should go through your model validation and model interpretation as usual. As we have already completed this in the previous exercise I’ll leave it up to you to decide whether you include it here (you should be able to just copy and paste the code). Please make sure you understand the biological interpretation of each of the parameter estimates and the interpretation of the hypotheses you are testing.

# Biologically: confirming what we already found out in the previous exercise:

# There is a significant interaction between the area of the patch and the level

# of grazing

# However, some observations are poorly predicted (fitted) using the set of

# available explanatory variables (i.e. the two very large forest patches)

# Interpretation:

# Bird abundance might increase with patch area due to populations being more

# viable in large patches (e.g. less prone to extinction),

# or perhaps because there is proportionally less edge effect in larger

# patches, and this in turn provides more high quality habitat for species

# associated with these habitat patches

# The negative effect of grazing may be due to grazing decreasing resource

# availability for birds, for example plants or seeds directly, or insects

# associated with the grazed plants. There may also be more disturbance of birds

# in highly grazed forest patches resulting in fewer foraging opportunities

# or chances to mate (this is all speculation mind you!).

# Methodologically:

# Doing model selection is difficult without intrinsic / expert knowledge

# of the system, to guide what variables to include.

# Even with this data set, many more models could have been formulated.

# For example, for me, theory would have suggested to test an interaction

# between YR.ISOL and LOGDIST (or LOGLDIST?),

# because LOGDIST will affect the dispersal of birds between patches

# (hence the colonisation rate), and the time since isolation of the patch may

# affect how important dispersal has been to maintain or rescue populations

# (for recently isolated patches, dispersal, and hence distance to nearest

# patches may have a less important effect)

OPTIONAL questions if you have time / energy / inclination!

A1. If we weren’t aiming to directly test the effect of the

LOGAREA:FGRAZE interaction statistically (i.e. test this

specific hypothesis), we could also have used AIC to perform model

selection. This time when we remove each term we are looking for the

model with the lowest AIC (remember that lower AIC values are better).

If you like, you can repeat the model selection you did above, starting

with the same most-complex model (M1) as before, but this time use the

drop1() function and perform model selection using AIC

instead (omitting the test = "F" argument), each time

removing the term that gives a model with a lower AIC.

drop1(M1)

## Single term deletions

##

## Model:

## ABUND ~ LOGDIST + LOGLDIST + YR.ISOL + ALT + LOGAREA + FGRAZE +

## FGRAZE:LOGAREA

## Df Sum of Sq RSS AIC

## <none> 1329.8 228.20

## LOGDIST 1 4.02 1333.8 226.40

## LOGLDIST 1 0.55 1330.3 226.23

## YR.ISOL 1 0.77 1330.6 226.24

## ALT 1 20.84 1350.6 227.24

## LOGAREA:FGRAZE 4 405.04 1734.8 238.02

#Removing the term 'LOGLDIST' gives the lowest AIC of 226.23

#So refit your model with this term removed. Run `drop1()` again on your updated model. Perhaps call this new model `M2.AIC`.

M2.AIC <- update(M1, formula = . ~ . - LOGLDIST)

drop1(M2.AIC) #removing which term gives the lowest AIC?

## Single term deletions

##

## Model:

## ABUND ~ LOGDIST + YR.ISOL + ALT + LOGAREA + FGRAZE + LOGAREA:FGRAZE

## Df Sum of Sq RSS AIC

## <none> 1330.3 226.23

## LOGDIST 1 3.64 1334.0 224.41

## YR.ISOL 1 0.78 1331.1 224.27

## ALT 1 22.24 1352.6 225.34

## LOGAREA:FGRAZE 4 406.74 1737.1 236.10

#Continue in this manner until removing any terms INCREASES the AIC. Then we have our minimal adequate model (which should be the same as the final model we finished with last time)

A2. However, the “superpower” of AIC is the ability to simultaneously compare multiple competing models, something we are not taking advantage of when we perform a stepwise model selection process. So, another approach to selecting our best model is to decide which set of models we are going to compare before we fit any of them, then fit them all, extract the AIC values, and see which model(s) have the lowest.

Fit 5 different models with the following terms, giving each model appropriate names to distinguish from the other models we have fitted so far: 1) “LOGLDIST + YR.ISOL + ALT + LOGAREA + FGRAZE + LOGAREA:FGRAZE”, 2) “LOGLDIST + YR.ISOL + ALT + LOGAREA + FGRAZE + LOGLDIST:YR.ISOL + LOGAREA:FGRAZE”, 3) “YR.ISOL + LOGAREA + FGRAZE”, 4) “LOGAREA + FGRAZE + LOGAREA:FGRAZE”, 5) “LOGAREA + FGRAZE”. If you like, you can add further models using combinations of terms you think might give the best model. Which model do you think will have the lowest AIC?

#Fit each model using the terms described above, giving each a unique and sensible name

M.AIC.1<- lm(ABUND ~ LOGLDIST + YR.ISOL + ALT + LOGAREA + FGRAZE + LOGAREA:FGRAZE, data= loyn)

M.AIC.2<- lm(ABUND ~ LOGLDIST + YR.ISOL + ALT + LOGAREA + FGRAZE + LOGLDIST:YR.ISOL + LOGAREA:FGRAZE, data= loyn)

M.AIC.3<- lm(ABUND ~ YR.ISOL + LOGAREA + FGRAZE, data= loyn)

M.AIC.4<- lm(ABUND ~ LOGAREA + FGRAZE + LOGAREA:FGRAZE, data= loyn)

M.AIC.5<- lm(ABUND ~ LOGAREA + FGRAZE, data= loyn)

A3. Now we have fitted our set of models, we can calculate the AIC of

each using the AIC() function. Which has the lowest? Which

has the highest? Are there any within 2 AIC of the lowest AIC? Are there

any models that differ in a single term and have an AIC difference of

about 2? What does this tell us about the additional term?

AIC(M.AIC.1)

## [1] 418.5422

#AIC of 418.54

AIC(M.AIC.2)

## [1] 420.3372

#AIC of 420.34

AIC(M.AIC.3)

## [1] 424.5987

#AIC of 424.60

AIC(M.AIC.4)

## [1] 413.7089

#AIC of 413.71

AIC(M.AIC.5)

## [1] 422.6052

#AIC of 422.61

#So the model with the lowest AIC (= 413.71) is M.AIC.4, with the terms 'LOGAREA + FGRAZE + LOGAREA:FGRAZE'

If all goes well, the best model should be

lm(ABUND ~ LOGAREA + FGRAZE + LOGAREA:FGRAZE). This is the

same model you ended up with when using the F test based model

selection in a stepwise manner. This might not always be the case and

generally speaking AIC based model selection approaches tend to favour

more complicated minimum adequate models compared to F test

based approaches.

We don’t need to re-validate or re-interpret the model, since we have already done this previously.

I guess the next question is how to present your results from the model selection process (using either F tests or AIC) in your paper and/or thesis chapter. One approach which I quite like is to construct a table which includes a description of all of our models and associated summary statistics. Let’s do this here for the AIC based model selection, but the same principles apply when using F tests (although you will be presenting F statistics and P values rather than AIC values).

Although you can use the output from the drop1() (and do

a bit more wrangling) let’s make it a little simpler by fitting all of

our models and then use the AIC() function to calculate the

AIC values for each model rather than drop1(). Note that

the values differ slightly between the two approaches; using either is

fine but best not to mix AIC values from the drop1() and AIC()

functions.

# This is one way of constructing a summary table for reporting the results:

# create a vector of the formulas for all the models compared during our model selection (remember to add any custom models you have have added yourself!):

model.formulas<- c(

"LOGLDIST + YR.ISOL + ALT + LOGAREA + FGRAZE + LOGAREA:FGRAZE",

"LOGLDIST + YR.ISOL + ALT + LOGAREA + FGRAZE + LOGLDIST:YR.ISOL + LOGAREA:FGRAZE",

"YR.ISOL + LOGAREA + FGRAZE",

"LOGAREA + FGRAZE + LOGAREA:FGRAZE",

"LOGAREA + FGRAZE")

#Collect the AIC values for each model (note they will be the 2nd column of the object 'model.AIC')

model.AIC = AIC(M.AIC.1, M.AIC.2, M.AIC.3, M.AIC.4, M.AIC.5) #these are the 5 models you already fitted in step A2 (plus any extra you added yourself)

# create a dataframe of models and AIC values

summary.table<- data.frame(Model = model.formulas,

AIC= round(model.AIC[,2], 2))

# Sort the models from lowest AIC (preferred) to highest (least preferred)

summary.table<- summary.table[order(summary.table$AIC), ]

# Add the difference in AIC with respect to best model

summary.table$deltaAIC<- summary.table$AIC - summary.table$AIC[1]

# print the dataframe to the console

summary.table

## Model AIC deltaAIC

## 4 LOGAREA + FGRAZE + LOGAREA:FGRAZE 413.71 0.00

## 1 LOGLDIST + YR.ISOL + ALT + LOGAREA + FGRAZE + LOGAREA:FGRAZE 418.54 4.83

## 2 LOGLDIST + YR.ISOL + ALT + LOGAREA + FGRAZE + LOGLDIST:YR.ISOL + LOGAREA:FGRAZE 420.34 6.63

## 5 LOGAREA + FGRAZE 422.61 8.90

## 3 YR.ISOL + LOGAREA + FGRAZE 424.60 10.89

Or if you prefer a prettier version to include directly in your paper

/ thesis. You will need to install the knitr package before

you can do this. See the ‘Installing R Markdown’ in Appendix A in the

Introduction to R book for more details.

| Model | AIC | deltaAIC |

|---|---|---|

| LOGAREA + FGRAZE + LOGAREA:FGRAZE | 413.71 | 0.00 |

| LOGLDIST + YR.ISOL + ALT + LOGAREA + FGRAZE + LOGAREA:FGRAZE | 418.54 | 4.83 |

| LOGLDIST + YR.ISOL + ALT + LOGAREA + FGRAZE + LOGLDIST:YR.ISOL + LOGAREA:FGRAZE | 420.34 | 6.63 |

| LOGAREA + FGRAZE | 422.61 | 8.90 |

| YR.ISOL + LOGAREA + FGRAZE | 424.60 | 10.89 |

Which model selection approach do you prefer? Can you think of pros and cons of either approach?

Whichever model selection approach you chose, what is key to remember is to perform a fully manual and thought-through model selection process, informed by the understanding of theory in the research area, and of the research questions, with rigorous model validation throughout.

End of the model selection exercise